ESO - European Southern Observatory logo.

2 March 2016

The sky around the star formation region RCW 106

In this huge new image clouds of crimson gas are illuminated by rare, massive stars that have only recently ignited and are still buried deep in thick dust clouds. These scorching-hot, very young stars are only fleeting characters on the cosmic stage and their origins remain mysterious. The vast nebula where these giants were born, along with its rich and fascinating surroundings, are captured here in fine detail by ESO’s VLT Survey Telescope (VST) at the Paranal Observatory in Chile.

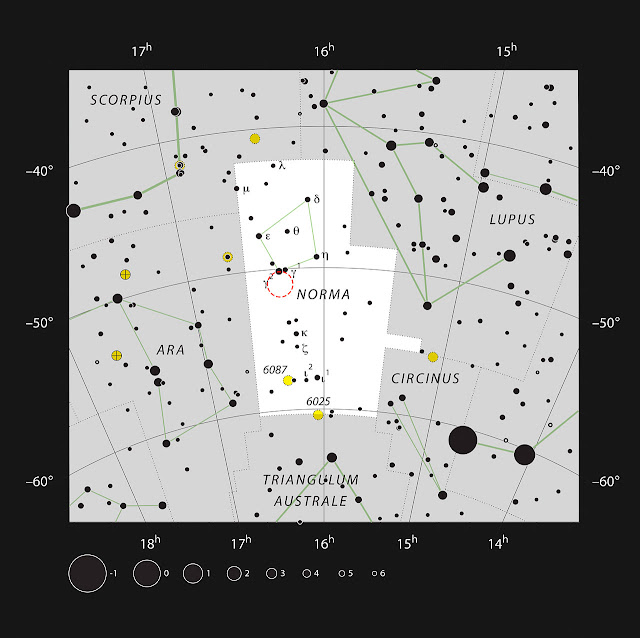

The sky around the star formation region RCW 106 (wide-field view)

RCW 106 is a sprawling cloud of gas and dust located about 12 000 light-years away in the southern constellation of Norma (The Carpenter’s Square). The region gets its name from being the 106th entry in a catalogue of H II regions in the southern Milky Way [1]. H II regions like RCW 106 are clouds of hydrogen gas that are being ionised by the intense starlight of scorching-hot, young stars, causing them to glow and display weird and wonderful shapes.

The sky around the star formation region RCW 106 (annotated)

RCW 106 itself is the red cloud above centre in this new image, although much of this huge H II region is hidden by dust and it is much more extensive than the visible part. Many other unrelated objects are also visible in this wide-field VST image. For example, the filaments to the right of the image are the remnants of an ancient supernova, and the glowing red filaments at the lower left surround an unusual and very hot star [2]. Patches of dark obscuring dust are also visible across the entire cosmic landscape.

Astronomers have been studying RCW 106 for some time, although it is not the crimson clouds that draw their attention, but rather the mysterious origin of the massive and powerful stars buried within. Although they are very bright, these stars cannot be seen in visible-light images such as this one as the surrounding dust is too thick, but they make their presence clear in images of the region at longer wavelengths.

The star formation region RCW 106 in the constellation of Norma

For less massive stars like the Sun the process that brings them into existence is quite well understood — as clouds of gas are pulled together under gravity, density and temperature increase, and nuclear fusion begins — but for the most massive stars buried in regions like RCW 106 this explanation does not seem to be fully adequate. These stars — known to astronomers as O-type stars — may have masses many dozens of times the mass of the Sun and it is not clear how they manage to gather, and keep together, enough gas to form.

A close look at the sky around the star formation region RCW 106

O-type stars likely form from the densest parts of the nebular clouds like RCW 106 and they are notoriously difficult to study. Apart from obscuration by dust, another challenge is the brevity of an O-type star’s life. They burn through their nuclear fuel in mere tens of millions of years, while the lightest stars have lifetimes that span many tens of billions of years. The difficulty of forming a star of this mass, and the shortness of their lifetimes, means that they are very rare — only one in every three million stars in our cosmic neighbourhood is an O-type star. None of those that do exist are close enough for detailed investigation and so the formation of these fleeting stellar giants remains mysterious, although their outsized influence is unmistakeable in glowing H II regions like this one.

Notes:

[1] The catalogue was compiled in 1960 by three astronomers from the Mount Stromlo Observatory in Australia whose surnames were Rodgers, Campbell and Whiteoak, hence the prefix RCW.

[2] The supernova remnant is SNR G332.4-00.4, also known as RCW 103. It is about 2000 years old. The lower filaments are RCW 104, surrounding the Wolf–Rayet star WR 75. Although these objects bear RCW numbers, detailed later investigations revealed that neither of them were HII regions.

More information:

ESO is the foremost intergovernmental astronomy organisation in Europe and the world’s most productive ground-based astronomical observatory by far. It is supported by 16 countries: Austria, Belgium, Brazil, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, along with the host state of Chile. ESO carries out an ambitious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful ground-based observing facilities enabling astronomers to make important scientific discoveries. ESO also plays a leading role in promoting and organising cooperation in astronomical research. ESO operates three unique world-class observing sites in Chile: La Silla, Paranal and Chajnantor. At Paranal, ESO operates the Very Large Telescope, the world’s most advanced visible-light astronomical observatory and two survey telescopes. VISTA works in the infrared and is the world’s largest survey telescope and the VLT Survey Telescope is the largest telescope designed to exclusively survey the skies in visible light. ESO is a major partner in ALMA, the largest astronomical project in existence. And on Cerro Armazones, close to Paranal, ESO is building the 39-metre European Extremely Large Telescope, the E-ELT, which will become “the world’s biggest eye on the sky”.

Related links:

O-type stars: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/O-type_star

Wolf–Rayet star: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wolf%E2%80%93Rayet_star

Mount Stromlo Observatory: http://rsaa.anu.edu.au/observatories/mount-stromlo-observatory

Links:

Photos of the VST: http://www.eso.org/public/teles-instr/surveytelescopes/vst/

For more information about the European Southern Observatory (ESO), visit: http://www.eso.org/public/

Images, Text, Credits: ESO/Richard Hook/IAU and Sky & Telescope/Video: ESO/Music: Johan B. Monell.

Greetings, Orbiter.ch