ISS - International Space Station logo.

Aug. 8, 2019

Each year, the president of the United States selects an elite group of scientists and engineers at the beginning of their independent research careers to receive the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers. This is the highest honor given by the U.S. government to outstanding science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) professionals at this point in their professions.

This year’s selection of 314 scientists includes 18 NASA researchers. Although these scientists are, as the award’s name indicates, early in their career, they have already built up impressive resumes. The list of accomplishments for three of them includes important contributions to research aboard the International Space Station.

International Space Station (ISS). Animation Credit: NASA

“The work of these three scientists is helping NASA enable human spaceflight exploration while making scientific discoveries. We benefit greatly from their research,” said Craig Kundrot, director of the Space Life and Physical Sciences Research and Applications division at NASA Headquarters. “Congratulations to Dr. Massa, Dr. Smith, and Dr. Barrila, and we look forward to them advancing the frontiers of knowledge in space biology.”

We sat down to chat with these three awardees, Jennifer Barrila, Ph.D., Gioia Massa, Ph.D. and David J. Smith, Ph.D., to learn more about how the orbiting laboratory has shaped their work.

Image above: Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers recipient and International Space Station researcher Jennifer Barrila. Photo courtesy of Jennifer Barrila.

Jennifer Barrila grew up in the 80s during the Space Shuttle Program. Her admiration for the people she saw flying to space inspired Barrila to pursue a career goal that most kids only dream of: becoming an astronaut. Many who share this daunting ambition focus on becoming aerospace engineers or pilots. But Barrila’s fascination for biology led her to a different path. “As I was finishing high school, the space station was being constructed,” says Barrila. “I knew when it was complete they would need scientists to perform experiments, so I decided to follow my passion and train in the biological sciences.”

While Barrila, who now works at Arizona State University, hasn’t yet gone to space, her research has made the trip. She has played integral roles in several experiments aboard the space station and a shuttle mission that studied how microgravity may alter infectious disease risks. Barrila co-led the first study to profile how human cells respond to Salmonella infection in space, served as a co-investigator on the first full-duration virulence study performed in space and is working on two experiments that could launch to the orbiting laboratory later this year.

She also was also part of a study that examined the impact of microgravity on Salmonella’s ability to infect a 3D cell culture model of the human colon. Barrila is now working to advance these models by incorporating fecal microbes collected from astronauts before, during and after spaceflight. “We're looking to see whether changes that occurred to the astronaut microbiome could possibly change their susceptibility to infection with Salmonella,” Barrila says. “I'm pretty excited about this study because we just don't know what we will see.”

While Barrila would still love to go to space, it is no longer her primary goal. “I went into this field wanting to become an astronaut, but doing the research has been so incredibly rewarding,” says Barrila. “Even if I never get to go into space, it’s been exciting to have the opportunity to contribute to the human spaceflight program.”

Image above: Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers recipient and International Space Station researcher Gioia Massa. Photo courtesy of Gioia Massa.

Gioia Massa grew up in Florida about an hour away from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral. After her middle school agriculture teacher was invited to Kennedy to learn about plant production for astronauts, he shared what he learned with Massa. “He brought back hours and hours of video. I was just completely captivated,” says Massa. “I think I watched all of it.”

From that springboard she chose to learn about hydroponics in high school, interned at Kennedy Space Center in the space life sciences training program and eventually earned her Ph.D. in Plant Biology from Penn State University. When a role for a NASA scientist opened up in 2013, Massa jumped at the opportunity.

Her work at NASA has built on her middle school passion of growing plants in space, looking at numerous aspects of agriculture in microgravity, specifically on the space station.

Image above: View of VEG-04 plant check, watering and weighing of harvested leaves in the Columbus Module. Image Credit: NASA.

She is studying the perfect conditions for plant growth in space and what species grow most effectively there. She is even getting feedback from the astronauts currently on board the station on which crops taste best. “Plants are very adaptable. They can really respond to the environment,” says Massa. “But getting that environment right is truly our hardest challenge. The biology is not as challenging as the physics to overcome.”

Right now, Massa and her team are focused on perfecting the cultivation of lettuce plants and a few other basic crops that they have learned to grow effectively. They hope to continue with their experiments on the space station and build on this knowledge to learn to grow more fruiting crops such as tomatoes and peppers. “To have an orbiting laboratory up there with astronauts continuously available to do science gives you a lot of power that you would otherwise not have. If you just do things one time, it leaves so many open questions,” says Massa. “Being able to do repeated evolutionary work on a platform like the space station is really the only way to advance these exploration systems.”

Image above: Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers recipient and International Space Station researcher David J. Smith. Photo courtesy of David J. Smith.

David J. Smith got a surprise call while in graduate school. On the other end was Crystal Jaing Ph.D., a researcher from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. “I couldn't believe my luck,” says Smith. “It was hard to believe, after having read all of her team’s literature, that she wanted to collaborate on something. She put together the dream team in microbiology.”

Jaing was recruiting a team for a new investigation of microbiology on the space station called Microbial Tracking-2. “Our goal is to identify any correlations of the microbiome community between what is in the space station versus what's on the astronauts to see if there is any microbial transfer and the potential impacts to crew health,” says Jaing.

While Smith’s previous research was based within our atmosphere, he shared an interest with Jaing in detecting microorganisms in challenging environments. “My work in graduate school was finding microbial signals in the upper atmosphere,” says Smith. “When Crystal put together this proposal, we knew that some of those microbes would also be floating around in spacecraft air. We thought we would bring some of the methodology from the open atmosphere here on Earth to the station.”

The year after finishing graduate school, Smith got a job working at Kennedy Space Center and helped finalize the proposal for Microbial Tracking-2.

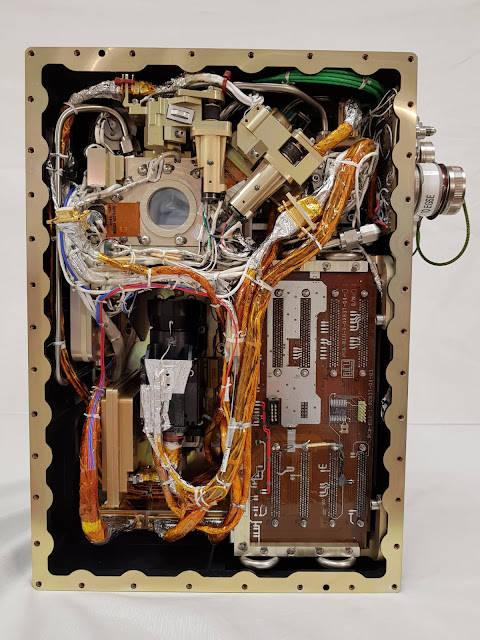

Image above: Microbial Tracking-2 hardware aboard the International Space Station, where it collects samples of the microbes and viruses floating in the air. Image Credit: NASA.

The Microbial Tracking team now has almost completed the sample collection period. Crew samples taken before, during and after flight, as well as environmental samples from station surfaces and air, make up the data. Smith and the research team will use this information to identify microbes and viruses on the orbital outpost and crew, and assess their disease-causing potential.

Smith sees this research in low-Earth orbit as a crucial step towards more than just preventing disease in space. He says it is needed to produce safe water, air and food systems on longer space missions to destinations like the Moon or Mars. “It’s going to be a whole different ball game when we go to deep space,” says Smith. “And it’s not going to be just macrosystems we have to be mindful of. It’s the invisible little passengers we bring along with us.”

The Space Life and Physical Sciences Research and Applications Division (SLPSRA) of NASA’s Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington funds the research of these three outstanding scientists.

Relate links:How human cells respond to Salmonella infection in space:

https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/research/experiments/explorer/Investigation.html?#id=790First full-duration virulence study performed in space:

https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/research/experiments/explorer/Investigation.html?#id=792Plant growth in space:

https://www.nasa.gov/content/growing-plants-in-spaceMicrobial Tracking-2:

https://www.nasa.gov/ames/research/space-biosciences/microbial-tracking-2Previous research:

https://aem.asm.org/content/aem/79/4/1134.full.pdfSpace Life and Physical Sciences Research and Applications Division (SLPSRA):

https://www.nasa.gov/directorates/heo/slpsra#_blankSpace Station Research and Technology:

https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/research/index.htmlInternational Space Station (ISS):

https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/main/index.htmlImages (mentioned), Animation (mentioned), Text, Credits: NASA/Michael Johnson/JSC/International Space Station Program Science Office/Erin Winick.

Best regards, Orbiter.ch