NASA logo.

March 23, 2023

Materials for coating spaceplanes maintain comfort in outerwear, sports uniforms, jeans

NASA intended its Reusable Launch Vehicle program of the 1990s to demonstrate technologies that would enable hypersonic spaceplanes to make affordable, repeated trips into space. It was never intended to improve the performance of hunting, skiing, and sports gear, but, more than 20 years after its cancellation, that’s what’s happened.

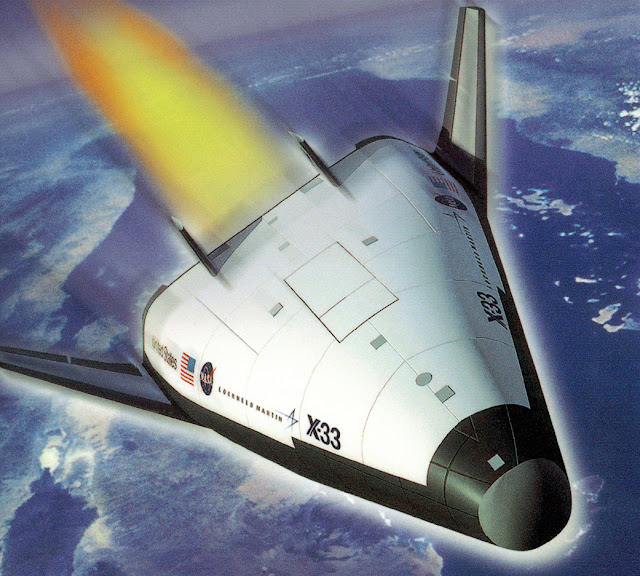

Image above: The Lockheed Martin X-33 X-plane, shown in this artist’s rendering, was intended to demonstrate technology pioneered under NASA’s Reusable Launch Vehicle program in the 1990s. The program was cancelled in 2001, but an emissive heat shield coating invented at Ames Research Center under the initiative has since found widespread commercial success as the Emisshield product line. Image Credit: NASA.

One of the program’s most successful spinoffs has been a substance dubbed Protective Coating for Ceramic Materials, or PCCM, which NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley, California, invented to protect the spaceplanes’ heat shields during atmospheric re-entry. NASA patented the coating, and Wessex Inc. – now known as Emisshield Inc. – licensed it and started developing commercial products.

The material isn’t a traditional insulator, and it’s not reflective. Instead, it has remarkably high emissivity, meaning it could absorb heat from a heat shield and radiate it away from the spacecraft. Emisshield has adapted PCCM into dozens of formulas now coating industrial equipment around the world (Spinoff 2001, 2004, 2011, 2019).

Image above: Around 2000, two ceramic tiles – one treated with an early version of Emissield and one untreated – were subjected to an oxyacetylene torch. The untreated tile, left, started beading after 30 seconds, while the one with the paper-thin layer of protection showed little damage after two minutes. Image Credit: NASA.

In 2013, Brad Poorman and Jim Hind incorporated Clean Textile Technology LLC, now of North Naples, Florida, and were looking for a niche in high-tech textiles when they learned of PCCM. They approached Emisshield, which agreed to license its technology exclusively to them for use in fabrics in exchange for a share in the brand.

By 2015, Trizar was up and running, with commercial partners turning out a combined 300,000 or so jackets that year (Spinoff 2016). Since then, the company has advanced its technology and worked its way into jeans, sports uniforms, and even face masks. In cold-weather gear, which is most of the company’s business, the material emits body heat back to the wearer. Trizar also produces low-emissivity formulas for hot weather, which reflect heat away from the body to keep people cool.

Image above: Artilect Systems now incorporates Trizar into the lining of many of its winter apparel items. Image Credit: Ali Vagini.

“During the pandemic, Emisshield was awarded patents around the fibers and fabrics we had developed, and we did a lot of R&D while the factories were shut down,” Poorman said.

At first, the emissive ingredients were printed onto fabrics, but the team has now devised ways to incorporate them into thread or yarn before it’s turned into cloth. “By getting it into the yarn, we’ve been able to deliver performance without adding any weight and with much less cost,” Poorman said.

Many commercial breakthroughs have come with these developments. A few years ago, Endeavor Athletic started using Trizar in some of its training apparel, and O’Neill put it into skiing and snowboarding jackets. Now customers can find Trizar materials in FORLOH hunting gear, Artilect Studio ski jackets and pants, KJUS jacket liners, Ergonomix apparel for hot and cold weather, Levi’s jeans sold in East Asia, and New Balance’s basketball and professional lacrosse uniforms.

Image above: The silver honeycomb print now found on the lining of many of Artilect’s jackets and other winter apparel is Trizar. Image Credit: Artilect Systems.

The company makes its emissive material concentrates in the United States before shipping them to textile mills around the world.

Trizar was growing at about 20% annually until the pandemic hit, and the pace has picked up to 30-40% annual growth since the return to a relative normal, Poorman said. And during the pandemic, Trizar was incorporated into high-end facemasks that sold over 100,000 units.

Poorman said Trizar’s popularity with consumers has helped it find new brands and markets. But its origins in the space program also don’t hurt, he said, noting that customers know space travel requires extreme temperature management. “Nowadays, everyone’s into NASA,” he added.

NASA has a long history of transferring technology to the private sector. The agency’s Spinoff publication profiles NASA technologies that have transformed into commercial products and services, demonstrating the broader benefits of America’s investment in its space program. Spinoff is a publication of the Technology Transfer program in NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate (STMD).

For more information on how NASA brings space technology down to Earth, visit:

https://spinoff.nasa.gov/

Related links:

Benefits to You: https://www.nasa.gov/topics/benefits/index.html

Space Tech: https://www.nasa.gov/topics/technology/index.html

Images (mentioned), Text, Credits: NASA/Loura Hall/NASA’s Spinoff Publication/By Mike DiCicco.

Greetings, Orbiter.ch