NASA - WISE Mission patch.

December 4, 2013

Astronomers have spotted what appear to be two supermassive black holes at the heart of a remote galaxy, circling each other like dance partners. The incredibly rare sighting was made with the help of NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE.

Follow-up observations with the Australian Telescope Compact Array near Narrabri, Australia, and the Gemini South telescope in Chile, revealed unusual features in the galaxy, including a lumpy jet thought to be the result of one black hole causing the jet of the other to sway.

"We think the jet of one black hole is being wiggled by the other, like a dance with ribbons," said Chao-Wei Tsai of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., who is lead author of a paper on the findings appearing in the Dec. 10 issue of Astrophysical Journal. "If so, it is likely the two black holes are fairly close and gravitationally entwined."

The findings could teach astronomers more about how supermassive black holes grow by merging with each other.

The WISE satellite scanned the entire sky twice in infrared wavelengths before being put into hibernation in 2011. NASA recently gave the spacecraft a second lease on life, waking it up to search for asteroids, in a project called NEOWISE.

The new study took advantage of previously released all-sky WISE data. Astronomers sifted through images of millions of actively feeding supermassive black holes spread throughout our sky before an oddball, also known as WISE J233237.05-505643.5, jumped out.

"At first we thought this galaxy's unusual properties seen by WISE might mean it was forming new stars at a furious rate," said Peter Eisenhardt, WISE project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., and a co-author of the study. "But on closer inspection, it looks more like the death spiral of merging giant black holes."

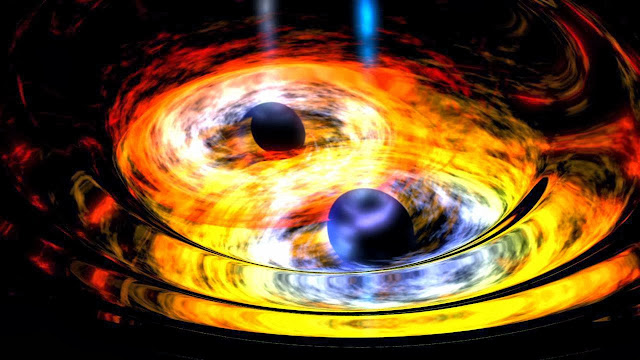

Two Black Holes on Way to Becoming One (Artist's Concept)

Image above: Two black holes are entwined in a gravitational tango in this artist's conception. Supermassive black holes at the hearts of galaxies are thought to form through the merging of smaller, yet still massive black holes, such as the ones depicted here. Image credit: NASA.

Almost every large galaxy is thought to harbor a supermassive black hole filled with the equivalent in mass of up to billions of suns. How did the black holes grow so large? One way is by swallowing ambient materials. Another way is through galactic cannibalism. When galaxies collide, their massive black holes sink to the center of the new structure, becoming locked in a gravitational tango. Eventually, they merge into one even-more-massive black hole.

The dance of these black hole duos starts out slowly, with the objects circling each other at a distance of about a few thousand light-years. So far, only a few handfuls of supermassive black holes have been conclusively identified in this early phase of merging. As the black holes continue to spiral in toward each other, they get closer, separated by just a few light-years.

It is these close-knit black holes, also called black hole binaries, that have been the hardest to find. The objects are usually too small to be resolved even by powerful telescopes. Only a few strong candidates have been identified to date, all relatively nearby. The new WISE J233237.05-505643.5 is a new candidate, and located much farther away, at 3.8 billion light-years from Earth.

Radio images with the Australian Telescope Compact Array were key to identifying the dual nature of WISE J233237.05-505643.5. Supermassive black holes at the cores of galaxies typically shoot out pencil-straight jets, but, in this case, the jet showed a zigzag pattern. According to the scientists, a second massive black hole could, in essence, be pushing its weight around to change the shape of the other black hole's jet.

NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE spacecraft (Artist's Concept)

Visible-light spectral data from the Gemini South telescope in Chile showed similar signs of abnormalities, thought to be the result of one black hole causing disk material surrounding the other black hole to clump. Together, these and other signs point to what is probably a fairly close-knit set of circling black holes, though the scientists can't say for sure how much distance separates them.

"We note some caution in interpreting this mysterious system," said Daniel Stern of JPL, a co-author of the study. "There are several extremely unusual properties to this system, from the multiple radio jets to the Gemini data, which indicate a highly perturbed disk of accreting material around the black hole, or holes. Two merging black holes, which should be a common event in the universe, would appear to be simplest explanation to explain all the current observations."

The final stage of merging black holes is predicted to send gravitational waves rippling through space and time. Researchers are actively searching for these waves using arrays of dead stars called pulsars in hopes of learning more about the veiled black hole dancers (see http://www.nasa.gov/centers/jpl/news/pulsar20131106.html ).

The technical paper is online at http://arxiv.org/abs/1310.2257 .

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., manages and operates the WISE mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. The WISE mission was selected competitively under NASA's Explorers Program managed by the agency's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. The science instrument was built by the Space Dynamics Laboratory in Logan, Utah. The spacecraft was built by Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp. in Boulder, Colo. Science operations and data processing take place at the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. Caltech manages JPL for NASA. More information is online at http://www.nasa.gov/wise and http://wise.astro.ucla.edu and http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/wise .

Images, Text, Credits: NASA / JPL / Whitney Clavin.

Greetings, Orbiter.ch