jeudi 25 octobre 2018

Final lap of the LHC track for protons in 2018

CERN - European Organization for Nuclear Research logo.

25 Oct 2018

Image above: View of the LHC accelerator in 2018. (Image: Maximilien Brice, Julien Ordan/CERN).

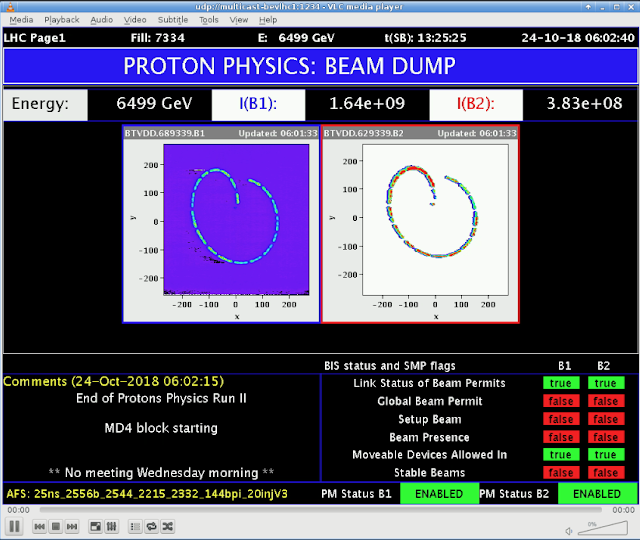

Today, protons said their goodbyes to the Large Hadron Collider during a last lap of the track. At 6 a.m., the beams from fill number 7334 were ejected towards the beam dumps. It was the LHC’s last proton run from now until 2021, as CERN’s accelerator complex will be shut down from 10 December to undergo a full renovation.

Image above: LHC Page1, showing the operational state of the accelerator at 6.02 a.m. on Wednesday 24 October. The spiral represents the proton bunches stopped by the beam dump (Image: CERN).

Now is the time for the scientists who read the collisions meter to make a first assessment. The integrated luminosity in 2018 (or the number of collisions likely to be produced during the 2018 run) reached 66 inverse femtobarns (fb-1) for ATLAS and CMS, which is 6 points better than expected. About 13 million billion potential collisions were delivered to the two experiments. LHCb accumulated 2.5 fb-1, more than the 2.0 predicted, and ALICE 27 inverse picobarns. The remarkable efficiency of the LHC this year is due to excellent machine availability and an instantaneous luminosity that regularly exceeded the nominal value. Since the start of the second run at a collision energy of 13 TeV, the integrated luminosity was 160 fb-1, higher than the 150 fb-1 expected.

Graphic above: This graph shows the integrated luminosity delivered to the ATLAS and CMS experiments during different LHC runs. The 2018 run produced 65 inverse femtobarns of data, which is 16 points more than in 2017. (Image: CERN)

However, this does not mean that the LHC runs are finished for this year. The show will go on for four more weeks, during which time the collider will master another kind of particle, lead ions (lead atoms that have been ionised, meaning they have had their electrons removed). After a few days of machine tests, the teams will inject these heavy ions, a run which have been prepared over recent months in the injectors. The collisions of lead ions allow studies to be conducted on quark-gluon plasma, a state of matter that is thought to have existed a few millionths of a second after the Big Bang.

Note:

CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, is one of the world’s largest and most respected centres for scientific research. Its business is fundamental physics, finding out what the Universe is made of and how it works. At CERN, the world’s largest and most complex scientific instruments are used to study the basic constituents of matter — the fundamental particles. By studying what happens when these particles collide, physicists learn about the laws of Nature.

The instruments used at CERN are particle accelerators and detectors. Accelerators boost beams of particles to high energies before they are made to collide with each other or with stationary targets. Detectors observe and record the results of these collisions.

Founded in 1954, the CERN Laboratory sits astride the Franco–Swiss border near Geneva. It was one of Europe’s first joint ventures and now has 22 Member States.

Related links:

Large Hadron Collider (LHC): https://home.web.cern.ch/fr/topics/large-hadron-collider

ATLAS: https://home.web.cern.ch/about/experiments/atlas

CMS: https://home.web.cern.ch/about/experiments/cms

ALICE: https://home.web.cern.ch/about/experiments/alice

LHCb: https://home.web.cern.ch/about/experiments/lhcb

For more information about European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), Visit: https://home.cern/

Images (mentioned), Graphic (mentioned), Text, Credits: CERN/Corinne Pralavorio.

Greetings, Orbiter.ch