CERN - European Organization for Nuclear Research logo.

In a first for particle physics, the CMS collaboration has observed three J/ψ particles emerging from a single collision between two protons

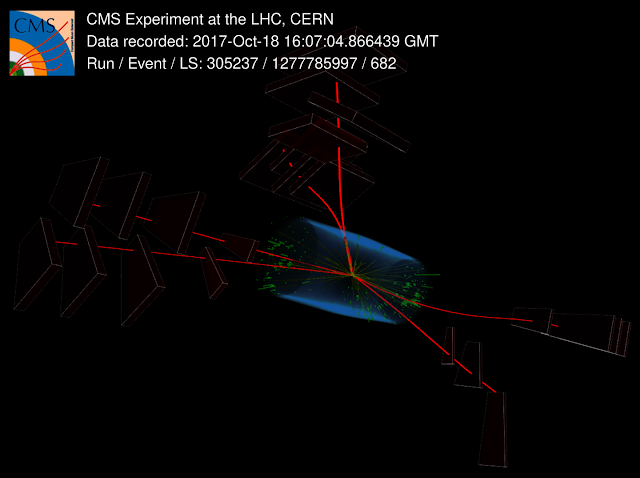

Image above: A proton–proton collision event with six muons (red lines) produced in the decays of three J/ψ particles. (Image: CMS/CERN).

It’s a triple treat. By sifting through data from particle collisions at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the CMS collaboration has seen not one, not two but three J/ψ particles emerging from a single collision between two protons. In addition to being a first for particle physics, the observation opens a new window into how quarks and gluons are distributed inside the proton.

The J/ψ particle is a special particle. It was the first particle containing a charm quark to be discovered, winning Burton Richter and Samuel Ting a Nobel prize in physics and helping to establish the quark model of composite particles called hadrons.

Experiments including ATLAS, CMS and LHCb at the LHC have previously seen one or two J/ψ particles coming out of a single particle collision, but never before have they seen the simultaneous production of three J/ψ particles – until the new CMS analysis.

Large Hadron Collider (LHC). Animation Credit: CERN

The trick? Analysing the vast amount of high-energy proton–proton collisions collected by the CMS detector during the second run of the LHC, and looking for the transformation of the J/ψ particles into pairs of muons, the heavier cousins of the electrons.

From this analysis, the CMS team identified five instances of single proton–proton collision events in which three J/ψ particles were produced simultaneously. The result has a statistical significance of more than five standard deviations – the threshold used to claim the observation of a particle or process in particle physics.

These three-J/ψ events are very rare. To get an idea, one-J/ψ events and two-J/ψ events are about 3.7 million and 1800 times more common, respectively. “But they are well worth investigating,” says CMS physicist Stefanos Leontsinis, “A larger sample of three-J/ψ events, which the LHC should be able to collect in the future, should allow us to improve our understanding of the internal structure of protons at small scales.”

Read more on the CMS website: https://cms.cern/news/trio-jps-particles-one-go

Note:

CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, is one of the world’s largest and most respected centres for scientific research. Its business is fundamental physics, finding out what the Universe is made of and how it works. At CERN, the world’s largest and most complex scientific instruments are used to study the basic constituents of matter — the fundamental particles. By studying what happens when these particles collide, physicists learn about the laws of Nature.

The instruments used at CERN are particle accelerators and detectors. Accelerators boost beams of particles to high energies before they are made to collide with each other or with stationary targets. Detectors observe and record the results of these collisions.

Founded in 1954, the CERN Laboratory sits astride the Franco–Swiss border near Geneva. It was one of Europe’s first joint ventures and now has 23 Member States.

Related links:

Large Hadron Collider (LHC): https://home.cern/science/accelerators/large-hadron-collider

ATLAS experiments: https://home.cern/science/experiments/atlas

CMS: experiments: https://home.cern/science/experiments/cms

LHCb experiments: https://home.cern/science/experiments/lhcb

For more information about European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), Visit: https://home.cern/

Image (mentioned), Animation (mentioned), Text, Credits: CERN/By Ana Lopes.

Greetings, Orbiter.ch